In recent years, California has been experiencing an increase in large fires due to a combination of factors, including drought conditions and a history of fire suppression. We saw this trend continue this summer with the Carr and Mendocino Complex Fires and even more recently this November with the Camp Fire. Fires tend to disproportionately affect rural communities that may already be experiencing economic and ecological hardships. While the Camp Fire was still smoldering 100 miles to the north, I traveled to Calaveras County as part of Sierra Institute’s socioeconomic work for ACCG to learn about the lasting impacts of another catastrophic fire, the Butte Fire, that occurred three years ago.

The Amador Calaveras Consensus Group, or ACCG, is a forest collaborative group whose boundaries encompass Amador and Calaveras Counties as well as parts of El Dorado and Alpine Counties, and include parts of the Stanislaus and Eldorado National Forests. It is one of twenty-three Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Projects, or CFLRs, around the country. The CFLR Program is unique in that it is one of the few natural resource-focused congressional funding programs to require socioeconomic monitoring. ACCG is contracting the Sierra Institute to conduct socioeconomic monitoring and report the results while guiding the group through the process so it can continue monitoring independently in the future.

Socioeconomic monitoring assesses social and economic conditions. It includes quantitative, or numerical, data such as employment rates, income levels, and school enrollment gathered from sources like the US Census. This type of data can show trends and correlations that we supplement with qualitative data, which includes information gathered through interviews with people who live in and have local knowledge about the area.

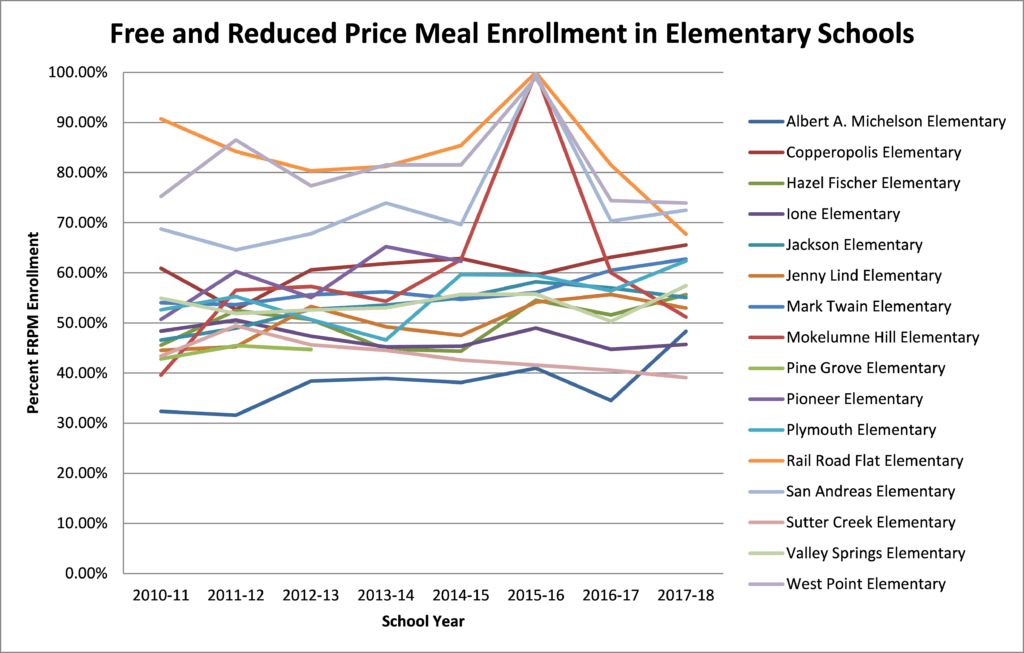

As an example, the graph above shows the percentage of students enrolled in the Free and Reduced Price Meal Program at public elementary schools in Amador and Calaveras Counties. Someone who is familiar with the area might be able to provide insight into the spike in enrollment at four schools in 2015. We know the Butte Fire occurred around that time but it is difficult if not impossible to establish causation from numbers alone. Stories are powerful and fill in a picture that quantitative data alone cannot capture. So, in November my supervisor Kyle and I headed down to the ACCG area to conduct interviews.

We talked to people who are members of ACCG, as well as people who do not have a direct connection to forest-related activities. We were invited to attend a community lunch in Mountain Ranch, a community heavily affected by the Butte Fire, and talked with residents about their experiences. We heard from some participants about issues similar to those in other rural, forested areas. For example, since mills have closed and timber jobs are no longer available, the major employers are the counties, casinos, hospitals, and the state prison in Ione. Otherwise people commute to Sacramento and other places in the valley or leave the area altogether, deflating the workforce capacity. For those in forest-related industries, fire risk is an important, on-going consideration, and in the burn area the Butte Fire continually comes up as a major factor in current socioeconomic conditions.

The Butte Fire burned 70,868 acres (mostly in Calaveras County and on private, non-industrial land), destroyed 921 structures including 549 homes, and resulted in 2 deaths in September of 2015. Three years later, the aftermath of the Butte Fire is still a shadow over the county. Some people have moved out of the area entirely, unwilling or unable to rebuild. For residents that stayed, living in the fire footprint and seeing the scorched land around them every day takes an emotional toll. In a county with a large retired population, many who live on large plots of land cannot physically clean up their properties themselves and it would be prohibitively expensive to hire a crew to do so, so dead trees still stand on acres upon acres, presenting a continued fire risk. Prospective marijuana growers took advantage of low real estate prices and moved into the area. This would be controversial in the best of circumstances, and the county government has only complicated it by first allowing and then banning marijuana cultivation. Despite these challenges, one positive outcome some interviewees mentioned is that fire tends to bring the community together to help one another.

The Camp Fire seems to have shaken residents of Amador and Calaveras Counties. Some are afraid, as one interviewee put it, of becoming “another Paradise.” With fires like the Butte and Camp Fires, the general public quickly returns to everyday life after the flames are put out and the smoke clears, but for communities in the fire’s path, like Mountain Ranch and Paradise, the process of recovery can be long and difficult. Socioeconomic monitoring may be able to help us understand these lasting social and economic impacts.

By: Hilary Sanders, Natural Resource Social Science Intern