When driving north on highway 89 toward Burney, looking out at miles of charred hills and dead trees that make up what is now the footprint of the Eiler Fire, you likely question if and how the forest might recover from such a severe burn. The Eiler Fire burned 32,416 acres of the Lassen National Forest in 2014, and has since catapulted an increasing number of conversations among land managers throughout the region regarding how to increase the scale of restoration and fuels reduction treatments across the landscape–and how to do it quickly. In this particular area, part of the answer is revealed when looking at the ground. Seemingly against all odds, there are buds of new growth. Saplings, from the Baker Cypress tree. Very rare saplings.

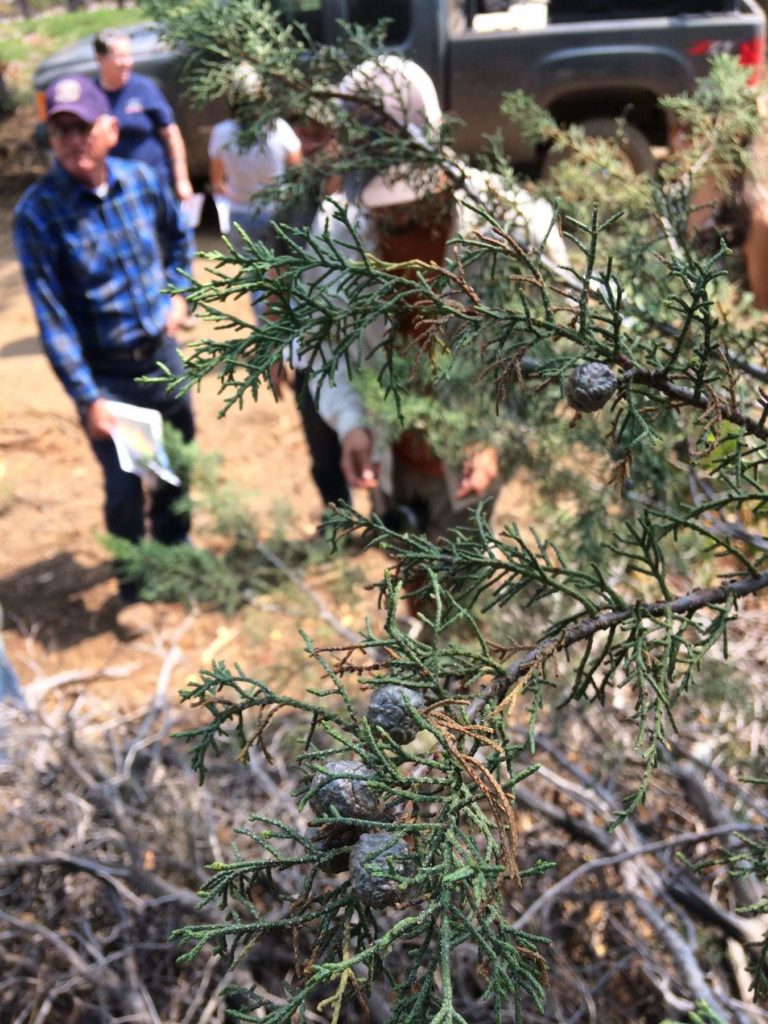

Baker Cypress love high severity, infrequent fire. They plan for it in a way that some of us might find extreme and possibly poor judgement on the part of evolution. Seeds of the next generation are reserved in sealed cones that accumulate on branches over the trees’ lifetime. They have peely bark that strips away and maintain low lying, dead branches which act in partnership as ladder fuel for fire to take hold.

If no fire or too frequent fire occurs, or the tree dies from any other cause, seeds wither without the possibility for germination and a massive amount of regeneration potential is lost. The Burney-Hat Creek Community Forest and Watershed Group (hereinafter, collaborative) saw this phenomenon when visiting a site where Baker Cypress became overtopped and starved for sunlight by competing conifers as a result of fire suppression.

If high severity fire does hit then most of the original Baker Cypress stand dies, but their cones open and are released onto the surrounding soil, shaking loose viable seeds. Serotiny refers to the ecological adaptation by some seed plants to reserve seeds until an environmental trigger occurs, like fire. While competitive plant life only adapted to low severity fire perishes, the serotinous species ensure survival.

On a smoky day around 10:00am, a group of collaborative members met at the Hat Creek Work Center. Academics from Humboldt State University, USFS resource specialists, local ecologists and community representatives came to Lassen National Forest for a tour of one of the eleven remaining Baker Cypress populations in the world. Hugh Safford, the regional ecologist for the USDA-Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region, Kyle Merriam, ecologist for Plumas and Lassen National Forests, and Janine Book, District Ranger for the Hat Creek Ranger District, led the field-based discussion regarding challenges and opportunities for management of Baker Cypress stands on the Lassen National Forest. Baker Cypress present a hugely important conservation issue with many questions as to implementation. One question being,

How do you balance Baker Cypress management with a landscape-scale management of mixed conifers?

Which leads us to another question,

Can we promote Baker Cypress growth while also making our forests fire resilient?

From this meeting, I learned the short answer is yes. Maybe. Due to climate change and anthropogenic disruption, high severity fire will continue to douse California, so there’s a need to first manage the forest landscape in a way that decreases the risk of uncontrollable burns. Thinning, cutting and mastication help shift the forest towards resilience. Afterwards, prescribed fire can be applied. An eventual goal would be to have a mixed fire regime containing units dominated by Baker Cypress, that burn as high severity, adjacent to units of pine, burning at low severity, and separated further by different fuel loading strategies. Baker Cypress would therefore receive a concentrated, pinpoint burn to encourage regeneration that doesn’t spread past fuel loading breaks. In the Burney area specifically, there’s a lot of active commercial management of forestland so project leaders are concerned about the interaction between species. Land will have to be managed differently depending on species composition so as to create a treatment system that allows Baker Cypress reproduction while protecting mixed conifer and other forest types. Managers don’t want an uncontrolled spread of Baker Cypress, rather, protection of current stands. The Forest Service must solve the riddle as to what type of techniques will actually work through experimentation and testing hypotheses.

The project we visited that day is called the Whittington Project. Spanning 3,277 acres, the land was planted as a plantation with the eventual goal of harvesting the wood for timber. Again, the theme of competing objectives of timber sales and Baker Cypress management challenges the choices foresters have for management. One option is use a combination of mastication and thinning regimes to create buffer zones around Baker Cypress populations. When fire doesn’t remove overtopping conifers and other shade tolerant species, the Baker Cypress slows its cone production until it eventually dies. It may produce tens of thousands of cones and millions of seeds but only about two seeds per cone actually contain viability. Radial thinning is then essential to remove encroaching trees, create gaps and expose Baker Cypress to sunlight. About halfway through the day, we visited a section of forest stand that had already undergone a treatment of mastication. Mastication looks like it sounds; chewed up shrubs and small trees (≤10 DBH) all mixed in with soils that have been purposefully disturbed. Piles of masticated debris get formed into windrows, basically pile lines. The idea is that mastication should release trees, change fire behavior by eliminating ladder fuels and decrease stand density. When the group discussed specifics of mastication, there was some doubt the technique was the best long term plan compared to the benefits of actual prescribed fire. Mastication creates a thick ground cover layer which raised concerns that the understory was prone to intense fire if debris becomes too dry. Forest Service members stressed that mastication only serves as a compromise in management for now, until a mixed fire regime can be safely implemented.

The conversation I heard that day was one of personal experience, on the part of the managing foresters attempting to implement management strategies and community members knowledgeable about fire, intermixed with highly scientific ecological analysis. Everyone shared a common language with which to communicate and every voice was heard. Collaborative members mentioned how informative this field visit was to finally have a visualization of forest areas they’ve only discussed in previous meetings. Forest Service representatives were more than happy to share preliminary plans for future management and field input from attendees. This was not just time to “talk at you” but a meeting that included feedback for planners and an assumption that you should ruminate on what you learned. Most importantly, a concrete plan for future collaboration seemed to naturally form. Monitoring plots led by Humboldt State University representatives might be placed in the mastication/ thinning areas to understand what treatments work. Kyle Merriam mentioned how fire modeling could provide valuable data, which elicited agreement from the group. Members also posed the possibility of performing NEPA on the Baker Cypress population. All of these ideas brought up possibilities to seek out additional support resources.

I’m new to Sierra Institute and the work of forest collaboratives, so watching this process in person shed a lot of light on the extent to which collaboratives operate. I saw a group that day where members offered a special niche of knowledge that complimented the next, even if there was discussion on the merits of what someone proposed. One collaborative member even told myself and another Sierra Institute representative that we would be “ some of the most knowledgeable citizens on the regional Baker Cypress situation after this meeting”. Not bad, in my opinion, for an afternoon. I see great potential for community awareness about the collaborative’s joint efforts with the Forest Service and the current predicament of the Baker Cypress tree. Hopefully, the Baker Cypress gets to stick around a little longer in the Sierra’s with their help.

If you would like to learn more about Baker Cypress, check the following links:

Saving the Cypress: Restoring Fire to Rare, At-Risk Species

https://www.firescience.gov/projects/briefs/06-2-1-17_FSBrief126.pdf

For the Baker Cypress, Fire Suppression Could be Fatal

http://now.humboldt.edu/news/for-the-baker-cypress-fire-suppression-could-be-fatal/

By Valerie Hurst

Valerie works as a Natural Resources and Social Science Intern for the Sierra Institute for Community and Environment.